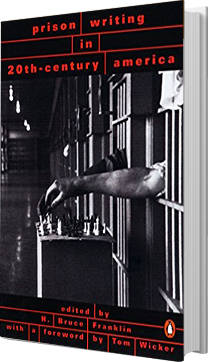

Prison Writing in 20th-Century America

Prison Writing in 20th-Century America

Includes work by: Jack London, Nelson Algren, Chester Himes,Jack Henry Abbott, Robert Lowell, Malcolm X, Mumia Abu-Jamal, and Piri Thomas.”

“Harrowing in their frank detail and desperate tone, the selections in this anthology pack an emotional wallop…Should be required reading for anyone concerned about the violence in our society and the high rate of recidivism.”—Publishers Weekly.

Prison Writing in 20th Century America

by Arnold Erickson

Prison has been a fertile setting for artists, musicians, and writers alike. Prisoners have produced hundreds of works that have encompassed a wide range of literature. Works by prisoners, such as Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, are counted among the great classics of literature. Books describing the prison experience, including the Autobiography of Malcolm X, inspired an audience far outside the prison walls. The importance of these works have been recognized in this country’s highest courts. See Simon & Schuster, Inc. v. New York State Crime Victim’s Compensation Board, 502 U.S. 105, 121-122 (1991)(citing works by prisoners). However, many of the finest prison writers remain unrecognized, and in some cases, unpublished.

H. Bruce Franklin‘s anthology, Prison Writing in 20th Century America, provides an important introduction to writers in prison. It includes both some of the most famous prison writing and that which remains relatively obscure. The writings focus on the prison experience itself, and provide a testimony to both the magnitude of the system and the struggle of human spirit.

Franklin places the prison system in a historical context. After slavery was abolished, prisons became the means to enforce servitude. The “Autobiography of an Imprisoned Peon,” published in 1904, vividly describes how a plantation was turned into an actual prison:

Every year many convicts were brought to the Senator’s camp from a certain county in Georgia, ‘way down in the turpentine district. The majority of these men were charged with adultery, which is an offense against the law of the great and sovereign State of Georgia!

The prisoners were housed in brutal stockades, whipped into submission, and forced to work on a large plantation.

This system was not limited to the South. Jack London describes time spent in the Erie County Penitentiary for vagrancy: a fifteen second trial and a thirty day sentence.

As for me, I was dazed. Here was I, under sentence, after a farce of a trial wherein I was denied not only my right of trial by jury, but my right to plead guilty or not guilty. Another thing my fathers had fought for flashed through my brain — habeas corpus. I’d show them. But when I asked for a lawyer, I was laughed at. Habeas corpus was all right, but of what good was it to me when I could communicate with no one outside the jail? But I’d show them. They couldn’t keep me in jail forever. Just wait till I got out, that was all. I’d make them sit up. I knew something about the law and my own rights, and I’d expose their maladministration of justice. Visions of damage suits and sensational newspaper headlines were dancing before my eyes when the jailers came in and began hustling us out into the main office.

London was put to work unloading barges on the Erie Canal and quickly became familiar with prison culture.

In the early part of this century, books by prisoners played an important role in inspiring reform. H.L. Mencken’s American Mercury magazine regularly printed works by notable prisoner authors, including works by Jim Tully and Ernest Booth that are found in this collection.

In 1934, Chester Himes published stories in Esquire while still a prisoner in Ohio State Penitentiary. His first story, “To What Red Hell,” described a fire that swept through the prison, written from the viewpoint of a white prisoner named “Blackie.”

Smoke rolled up from the burning cell block in black, fire-tinged waves. The wind caught it and pushed it down over the prison yard like a thick, gray shroud, so low you could reach up and touch it with your right hand. Flames, seen through the mist of smoke, were devils’ tongues stuck out at the black night. . . When Blackie turned left by the dining room he had an odd feeling that he could hear those men a hundred yards away crying “Oh God! Save me! Oh God! Save me!” over and over again. The words spun a sudden fear in his mind.

After his parole, Himes achieved critical acclaim in both the United States and Europe. Yet, it took until 1998 for his novel about his prison experience to be published, fourteen years after his death.

The success of many prisoner writers came with a price. Herman Specter, the senior librarian at San Quentin, wrote that there was a counterflow of reaction and prohibition. Prisoners were to be punished and were not to make money. Writing became banned and prisons were searched for manuscripts to be confiscated and destroyed — a system that lasted in California until death row prisoner Caryl Chessman smuggled out his manuscripts and helped break down the barriers that prevented prisoners from writing. It was not until 1968 that the state legislature formally abandoned the idea of “civil death” and afforded protection to manuscripts written by prisoners.

A different type of prison writing began to emerge. The Autobiography of Malcom X described the transformation of a common criminal into a Muslim who was destined to become one of the most significant leaders in modern American history. George Jackson’s Soledad Brother provided a witness that made the prison movement a part of the radical left:

This camp brings out the very best in brothers or destroys them entirely. But none are unaffected. None who leave here are normal. If I leave here alive, I’ll leave nothing behind. They’ll never count me among the broken men, but I can’t say that I am normal either. I’ve been hungry too long. I’ve gotten angry too often. I’ve been lied to and insulted too many times. They’ve pushed me over the line from which there can be no retreat. I know that they will not be satisfied until they’ve pushed me out of this existence altogether.

A new era in prison writing began to emerge as prisoners found a voice that at least some in the outside world were willing to hear. Malcom Braly’s On the Yard was labeled by Kurt Vonnegut as the “great American prison novel.” Etheridge Knight achieved wide recognition for his poetry, beginning with his first volume, Poems from Prison published in 1968:

The warden said to me the other day

why come the black boys don’t run off

like the white boys do?”

I lowered my jaw and scratched my head

and said (innocently, I think), “Well, suh,

I ain’t for sure, but I reckon it’s cause

we ain’t got nowhere to run to.”

The writers of the modern renaissance include Patricia McConnel, Jerome Washington, Dannie Martin, and Mumia Abu-Jamal. They speak in eloquent and rich voices. Yet, there is a constant struggle to be heard. The federal Bureau of Prisons successfully prevented Martin from writing under this own by-line in the San Francisco Chronicle. Right wing flurry forced the National Public Radio to withdraw its presentation of Abu-Jamal’s commentaries.

The selections in this book remind us both about how much and how little prison has changed. A Jack London may no longer be in danger of being forced to unload barges, yet the growth of private prisons, prison industrial authorities, and joint venture programs firmly retain the role of profit in the criminal justice system. The sheer growth of prisons and the call for harsher punishment has ended many of the programs that helped writers find their voice, yet writing will undoubtedly continue to emerge even as it did under similar conditions in the past.

Franklin’s anthology comes at a time when the criminal justice system needs to be re-examined. He reminds us that we are not that distant from when a black youth in Alabama was sentenced to life for stealing $1.50. How much different is it when other youth are sentenced to life imprisonment under our three strikes law after stealing a pack of cigarettes or selling $20 worth of cocaine? The prison experience seems destined to shape our society. For many it is the past, present, and future of what life will hold. For all, it requires critical choices about how our resources can best be used.

The anthology offers a view of over the prison wall. This view is needed all the more because media access has been sharply restricted in California prisons. It is the voice of the prisoner that alone may bring their experience to the public. The voice that Franklin presents is always provocative, often disturbing, and in some cases, inspiring. As Franklin concludes:

In the twilight of the twentieth century, the United States, birthplace of the modern prison two centuries earlier, has transformed the prison into a central institution of society, unprecedented in scale and influence. Out of this transformation has come another kind of writing, far more bleak and desperate than the prison literature of any earlier period. And yet even these works, rising like their forerunners from the depths of degradation, reveal the creativity and strength of humanity.

Prison Writing in 20th-Century America, edited by H. Bruce Franklin. Forward by Tom Wicker. Penguin Books, 1998.